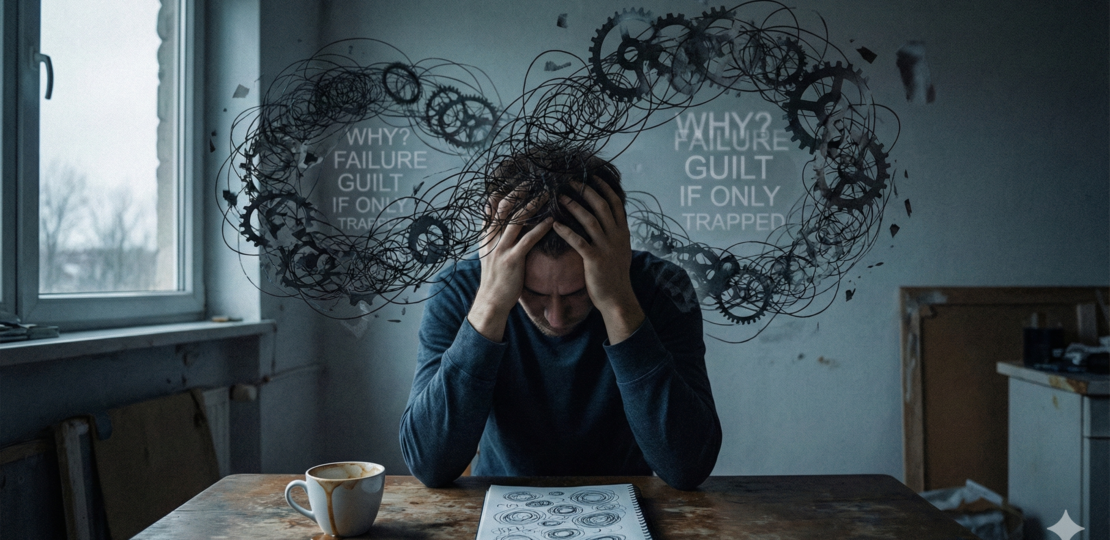

Depression is often talked about as sadness, exhaustion, or numbness, but one of its most quietly corrosive features is rumination—the mental loop that replays the same painful thought with the persistence of a scratched vinyl record. Rumination isn’t the dramatic storm most people imagine when they picture depression. It’s more like the slow drip of a leaky faucet at 3 a.m., endlessly repetitive, somehow both trivial and impossible to ignore. The mind keeps returning to the same regrets, the same imagined futures, the same internal criticisms, as if believing the right angle of inspection will conjure relief.

What makes rumination particularly insidious is how rational it feels from the inside. People who ruminate often believe they’re “problem-solving,” even as their thoughts circle with no exit ramp. Neuroscientists point toward the default mode network—the brain’s introspective system—which becomes hyperactive during these loops. It’s the same network that helps create our sense of self, so when it starts spinning, the self becomes a hall of mirrors. A tiny memory from years ago can suddenly feel unbearably important, replayed until it’s worn down to an emotional nub.

The tricky part is that rumination and depression feed each other like two vines tangled on the same trellis. Constant mental replay deepens feelings of hopelessness, and that hopelessness, in turn, makes the rumination feel even more convincing. It’s not just thinking too much; it’s thinking in a way that tightens the knot each time you try to loosen it. People caught in this loop often describe feeling “stuck in their own head,” as if the world outside has dimmed and all that’s left is the internal echo chamber.

Understanding rumination reminds us how delicate the architecture of thinking really is. The brain is always trying to make meaning, even when meaning is unavailable. It tries to solve problems even when no solution exists. Rumination is that attempt turned inward on itself. When readers learn about it, they often recognize a piece of themselves—a mental habit that flirts with disorder even in healthy minds. Exploring this phenomenon invites a broader reflection on how we narrate our inner lives, and how those narratives can sometimes lead us into emotional cul-de-sacs rather than out of them.

RELATED POSTS

View all