Welcome back. This is chapter 13 of the Psychology of Money.

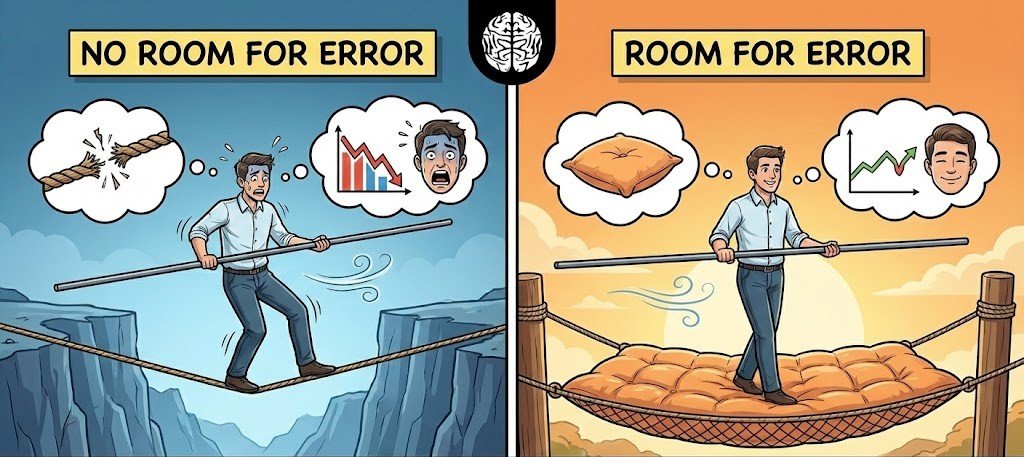

Chapter 13: Room for Error

The most important part of any plan is not the plan itself, but the quiet assumption that it won’t unfold the way you expect. Hope and preparation live in different rooms of the mind. You can hope to be right, and still design your life as if you’ll be wrong. That tension isn’t hypocrisy; it’s maturity. Certainty feels good, but durability comes from acknowledging that the world doesn’t owe you coherence.

Most mistakes happen when good ideas are pushed too far. Optimization and confidence in models are perfect examples. Both are useful—until they aren’t. Optimization assumes the environment stays stable long enough for fine-tuning to matter. Models assume the variables we can measure are the ones that matter most. Reality, with a sense of humor bordering on cruelty, often rearranges those assumptions without warning. When that happens, tightly optimized systems don’t bend; they snap.

Room for error is not a mathematical concept first—it’s an emotional one. If you feel safe, you’re more likely to act rationally when things go wrong. That emotional safety usually rests on numerical buffers and situational flexibility, but the goal isn’t the numbers themselves. The goal is staying calm enough to continue playing the game. Panic is expensive. Fragility compounds losses.

This is why aiming lower than your maximum potential isn’t weakness. It’s stability. Preparing for 60–75% of the worst plausible outcome doesn’t mean expecting disaster; it means respecting the possibility of it. Stability buys time. Time allows recovery. Recovery allows learning. Learning is what turns bad luck into survivable mistakes instead of permanent scars.

People dislike ranges. They prefer targets. A single number feels authoritative, decisive, confident. Ranges feel like hedging. In finance—and in life—this preference is dangerous. It reflects a discomfort with uncertainty rather than an understanding of it. The future doesn’t arrive as a point estimate. It arrives as a distribution of outcomes, most of which don’t look like the neat stories we tell in advance.

One reason people avoid room for error is the belief that someone, somewhere, must know what’s coming. If that were true, then leaving slack on the table would feel irresponsible. But believing you know the future is far more dangerous than admitting you don’t. Confidence without humility invites overcommitment, and overcommitment turns small errors into fatal ones.

Modern systems are fascinating here. They’re often more robust than older ones, yet capable of failing in much bigger ways. Technology reduces small mishaps while quietly enabling large, systemic ones. The mouse that disabled a tank in Stalingrad is a reminder: failure doesn’t need to be elegant. It just needs to exploit a dependency you didn’t think mattered.

Which is why single points of failure are so risky. Efficiency loves them. Resilience hates them. When too much depends on one assumption, one skill, one system, or one career path, the cost of being wrong skyrockets. A hyperspecialized degree can be powerful—until it isn’t. If the career disappoints or the field shifts, the lack of alternatives becomes the real problem. Flexibility is not indecision; it’s insurance.

Note: I am reiterating myself if you missed my previous posts. I have specifically not included any direct example or quote from the book for two reasons.

A. I don’t want to be accused of plagiarism.

B. These posts are the public copy of my thoughts, not Morgan Housel’s thoughts.

RELATED POSTS

View all