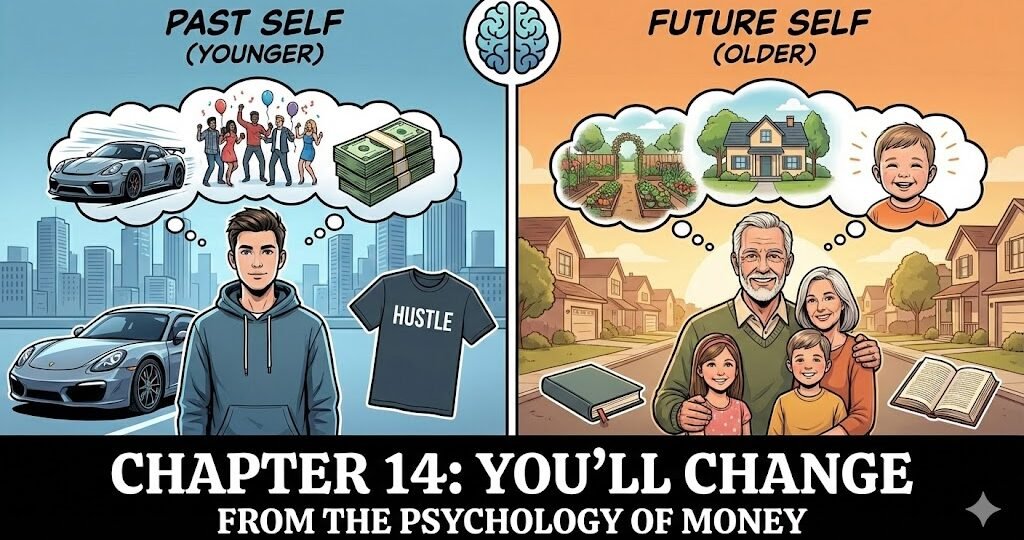

Welcome back. This is chapter 14 of the Psychology of Money. It talks about how we change, and we must too. Didn’t understand? Read on.

Chapter 14: You’ll Change

Long-term planning is harder than it looks, not because the world is unpredictable, but because you are. Imagining a future goal is easy when it’s abstract. Imagining that same goal under the weight of stress, competition, fatigue, and changing priorities is a different exercise entirely. Most plans fail not because life interferes, but because the person who made the plan no longer exists in the same form.

A large part of this blindness comes from a mix of ego and cognitive limitation. We are good at seeing how much we’ve changed in the past, yet oddly confident that we’ve now arrived at a final version of ourselves. In some cultures, social pressure amplifies this illusion. Choices are expected to be decisive and permanent. Admitting uncertainty is mistaken for weakness, when in reality it’s a more accurate reading of human nature.

The data around careers quietly reinforces this truth. Many people don’t end up working in fields related to what they studied, not always because of failure or poor choices, but because what they wanted at eighteen isn’t what they want at thirty. That change isn’t inherently bad. It becomes a problem only when the original decision was made without adequate exploration or reflection. Change after thoughtful planning is evolution. Change after blind commitment is damage control. The difference matters.

This is where the idea of sunk cost becomes dangerous. We often stay in paths we’ve outgrown simply because we’ve already paid for them—with time, money, or effort. But sunk costs are not anchors; they’re receipts. They prove you tried, not that you must continue. A useful way to think about this is to set thresholds in advance. Just as an investor decides beforehand when to exit a losing position, life decisions need similar guardrails. If things deteriorate beyond a pre-decided point—financially, mentally, or emotionally—it’s not quitting. It’s adjusting the plan.

Financially, this also argues against extremes. Obsessively chasing millions assumes you’ll want the same sacrifices forever. Settling too early for minimal comfort assumes frugality alone guarantees fulfillment. Both are rigid bets on a future self you don’t fully understand yet. Moderation leaves room to pivot. It reduces regret on either end.

Accepting that you’ll change doesn’t mean lowering ambition. It means loosening your grip on how ambition must look. Direction matters more than form. Progress doesn’t always move in straight lines, and changing your mind isn’t a betrayal of your past self—it’s a continuation of growth. Life isn’t a fixed contract signed at eighteen. It’s a draft that gets better when you allow revisions.

RELATED POSTS

View all