Welcome back. This is chapter 17 of the Psychology of Money. This is yet another perspective shifting chapter, focusing on optimism and its compelling sibling: pessimism.

Chapter 17: The Seduction of Pessimism

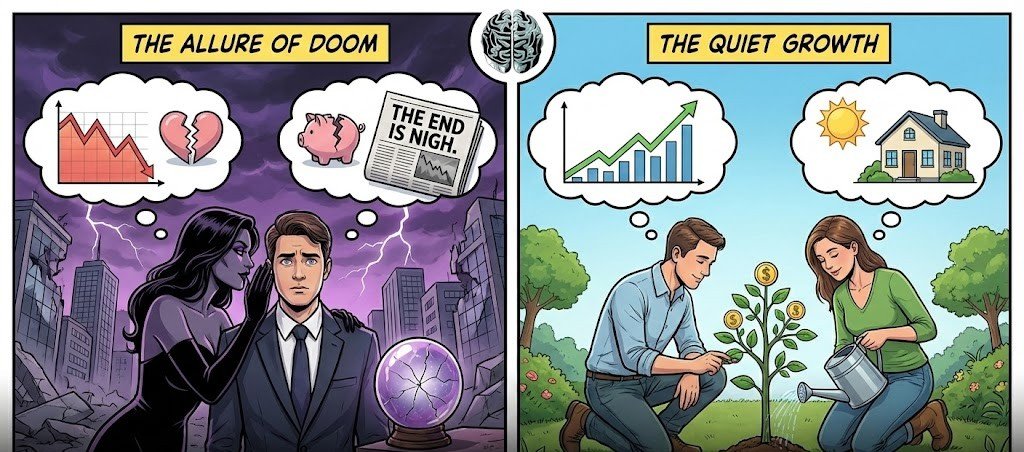

Pessimism has a strange advantage: it sounds intelligent. It feels cautious, informed, even caring. Optimism, by contrast, often sounds like a sales pitch—smooth, suspicious, and a little naïve. This imbalance isn’t accidental. It’s the result of two forces working together: deep cognitive wiring and powerful social reinforcement.

On the cognitive side, pessimism is ancient. For most of human history, the cost of ignoring danger was death, while the cost of ignoring opportunity was usually just inconvenience. Natural selection rewarded those who treated threats as urgent and opportunities as optional. That bias never left us. It merely learned new costumes—market crashes, recessions, geopolitical collapse—while keeping the same emotional circuitry intact.

Socially, pessimism has been trained and amplified. Warning others makes you sound helpful. Predicting disaster makes you sound serious. And when the disaster doesn’t arrive, relief replaces accountability. People rarely ask why the warning was wrong; they simply feel glad it didn’t come true and move on to the next alarm. That emotional payoff—relief without consequence—is one of pessimism’s most underappreciated rewards.

Optimism, meanwhile, is widely misunderstood. Real optimism is not the belief that everything will be fine. It’s the belief that, over time, the odds tilt toward improvement—even if the path is messy, uneven, and punctuated by setbacks. It’s not simple. It’s not guaranteed. It’s just a reasonable bet in a world that adapts, learns, and compounds.

One reason pessimism feels more convincing is speed. Bad news arrives all at once. Crashes, wars, and failures happen fast and demand attention. Progress creeps. It compounds quietly, often invisibly, until decades later it looks obvious in hindsight. There are countless overnight tragedies. There are almost no overnight miracles.

Another reason is extrapolation. Pessimists often project current trends forward without accounting for adaptation. But markets, societies, and technologies respond. Extremely good and extremely bad conditions rarely persist for long, because incentives shift and behavior follows. The future is rarely a straight line drawn from the present, even though that’s the easiest line to imagine.

Modern media leans heavily into pessimism because it works. Fear captures attention. Attention converts to clicks. And money, unlike optimism, is immediate and measurable. Concern for risk exists, but profitability does most of the driving.

The irony is that expecting things to be bad often feels safer, but it can quietly distort decision-making. Optimism tempered by realism isn’t blindness; it’s resilience. It accepts uncertainty without surrendering to it. It acknowledges risk without assuming doom.

Expecting the world to fall apart makes you feel prepared. Expecting it to adapt makes you patient. History suggests patience has been the better long-term strategy—even if it never sounds as clever in the moment.

RELATED POSTS

View all