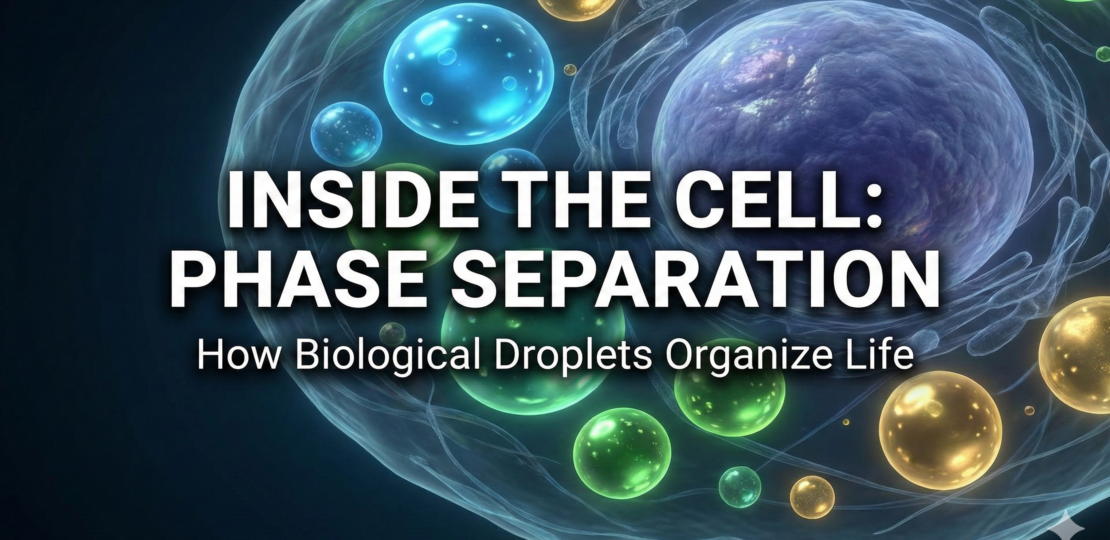

For a long time, biology imagined the cell as a tidy bag of membrane-bound compartments: nucleus here, mitochondria there, everything neatly wrapped. Then researchers noticed something unsettling. Many important cellular structures have no membranes at all—and yet they are clearly organized. They appear, disappear, fuse, and flow like droplets of oil in water. This phenomenon is called biomolecular phase separation.

Phase separation happens when certain proteins and RNAs stick to each other weakly but collectively, forming dense liquid-like clusters. These clusters, often called biomolecular condensates, concentrate specific molecules while excluding others. The nucleolus, where ribosomes are assembled, is a classic example. Stress granules, which form when cells are under pressure, are another. No walls, no doors—just physics doing the sorting.

What makes this unfamiliar is that it blurs the line between chemistry and cell biology. The same rules that govern salad dressing separating into layers help explain how cells organize reactions in space and time. By forming a droplet, a cell can speed up certain reactions simply by bringing the right molecules close together, then dissolve the droplet when it is no longer needed.

There is a darker edge to this elegance. When phase separation goes wrong, liquid droplets can harden into solid aggregates. This transition is linked to neurodegenerative diseases like ALS and Alzheimer’s. The same forces that allow flexible organization can, under stress or mutation, lock molecules into toxic states. Cells, it turns out, are not just chemical factories—they are soft-matter systems, balancing delicately between order and collapse.

RELATED POSTS

View all