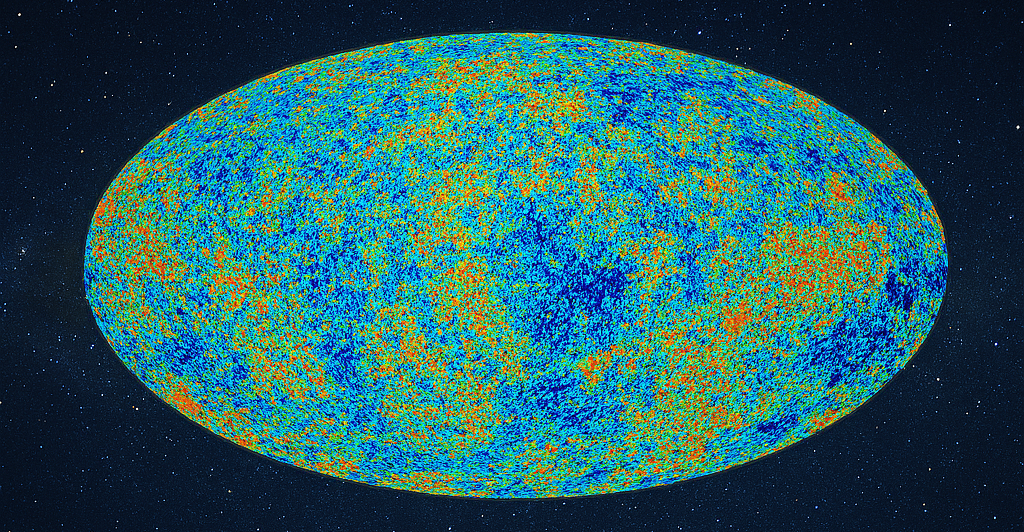

Long after a campfire goes out, you can still feel a faint warmth in the air. The universe has its own version of that leftover heat, and scientists call it the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, or CMB. It’s essentially the afterglow of the Big Bang—the faint light that has been traveling through space for nearly 14 billion years.

The CMB wasn’t discovered through fancy telescopes or grand cosmic theories, but rather by accident. In 1965, two engineers, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, were working on a radio antenna in New Jersey. They kept picking up a strange background noise, no matter which way they turned their antenna. At first, they thought it was a technical issue, even blaming pigeon droppings inside the equipment. But soon, they realized they had stumbled onto something extraordinary: the very “echo” of the universe’s beginning.

What makes this radiation so important is that it provides scientists with a snapshot of the early universe. Back then, the universe was hot and dense, filled with glowing plasma. As it expanded and cooled, light was finally able to travel freely—and that light is what we now detect as the CMB. It has stretched over billions of years into microwave wavelengths, which are invisible to our eyes but detectable with the right instruments.

In simple terms, the CMB is the universe’s baby picture. Just like an old family photograph can reveal what someone looked like long ago, the CMB shows us what the cosmos looked like in its infancy. By studying it, scientists can piece together the story of how galaxies, stars, and eventually life itself came to be.

RELATED POSTS

View all