When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, the world’s economy fell into chaos. Factories shut down, unemployment soared, and millions of people went hungry — not because there wasn’t enough work to do, but because no one could afford to pay for it. Traditional economists, still loyal to Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,” believed the economy would eventually fix itself. John Maynard Keynes disagreed — and his ideas would rewrite economic thinking for the next century.

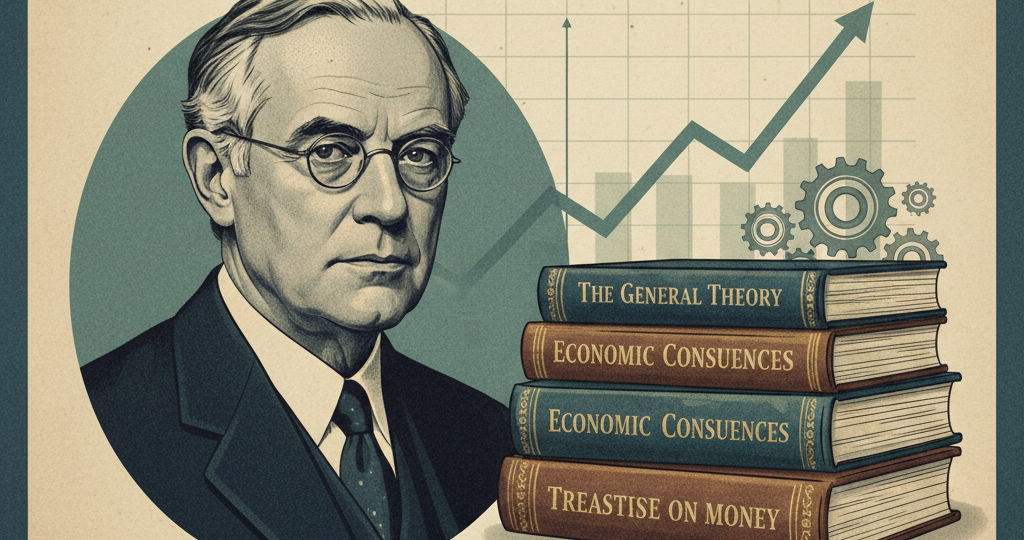

Keynes, a British economist with a flair for both mathematics and wit, introduced a radical concept: sometimes, markets need help. In his landmark book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), he argued that during economic downturns, people stop spending out of fear. Businesses then cut production, lay off workers, and the cycle worsens. The solution? The government must step in — spend money, create jobs, and kick-start demand again.

This became known as Keynesian economics, and it shaped modern economic policy. His theory justified public projects, social programs, and stimulus packages as legitimate tools to stabilize economies. Instead of waiting for recovery, Keynes urged leaders to act boldly — to “prime the pump,” as he put it, and restore confidence.

Keynes’s ideas helped guide governments during World War II and the postwar rebuilding period, laying the foundation for the modern welfare state. He was also instrumental in establishing the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, helping rebuild global financial stability.

He wasn’t just a theorist buried in papers — he was a sharp debater, a lover of art and culture, and someone who believed economics should serve humanity, not the other way around. Keynes’s greatest legacy is simple but profound: when economies freeze, courage — not caution — is what gets them moving again.

RELATED POSTS

View all