The Gambler’s Fallacy is exactly what it sounds like. It’s a bias that gamblers, and many others, fall into every day. When a gambler keeps losing, what does he do? He keeps betting, and somehow he believes his chances are better since he’s lost money. Let me tell you a simpler example. If you’ve ever tossed a coin multiple times, and you keep getting one side, let’s say heads, you would expect, at least in that moment, to get tails more than heads the next toss, right? But every time you toss a coin, it’s 50/50. Just because you’ve tossed it a few times before, it doesn’t change the odds; chances don’t have memory.

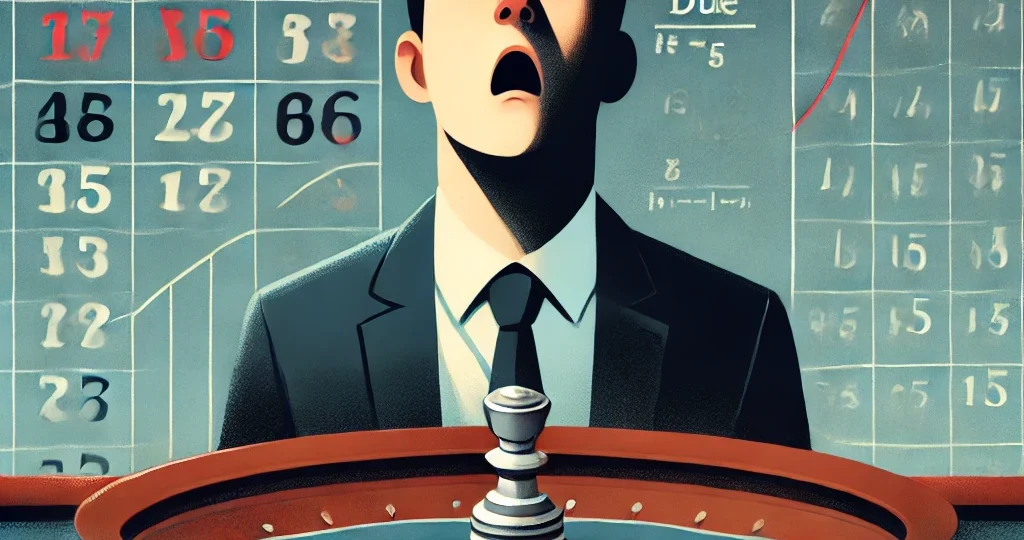

The research behind this fallacy comes from Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. I’ve mentioned this before in the System 1 vs System 2 blog post, but Dan Kahneman is a psychologist who won a Nobel prize in behavioral economics, but he did not take a single economics course. The sad thing is Amos Tversky died before the Nobel was announced, so only Dan Kahneman got it, even though it was both of their efforts that pioneered that research. There’s no specific experiment that I’ve come across about this topic so I am not going to discuss it here. Although, there is one famous example of the Gambler’s Fallacy. It happened in 1913 in Monte Carlo Casino, when a roulette wheel landed on black 26 consecutive times. As the streak continued, gamblers believed red was ‘overdue’ and started placing huge bets on red, despite the chances being exactly the same for every spin.

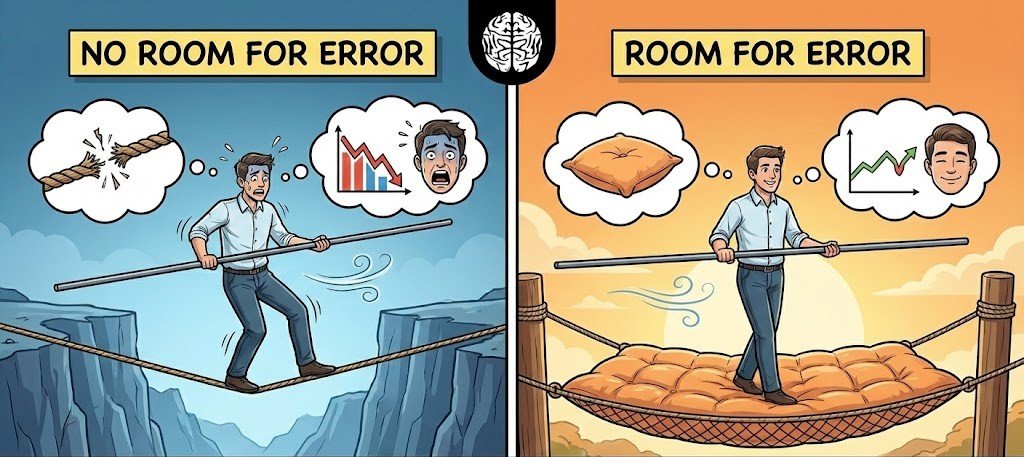

Well, how to avoid the Gambler’s Fallacy? To avoid the gambler’s fallacy, people must understand that random events do not have memory—each outcome is independent, and probabilities remain unchanged no matter what has happened before.

RELATED POSTS

View all