Welcome back. This is chapter 4 of the Psychology of Money. It talks about a rather simple-looking concept, Compounding, and its exceptional rewards when understood and used.

Chapter 4: Confounding Compounding

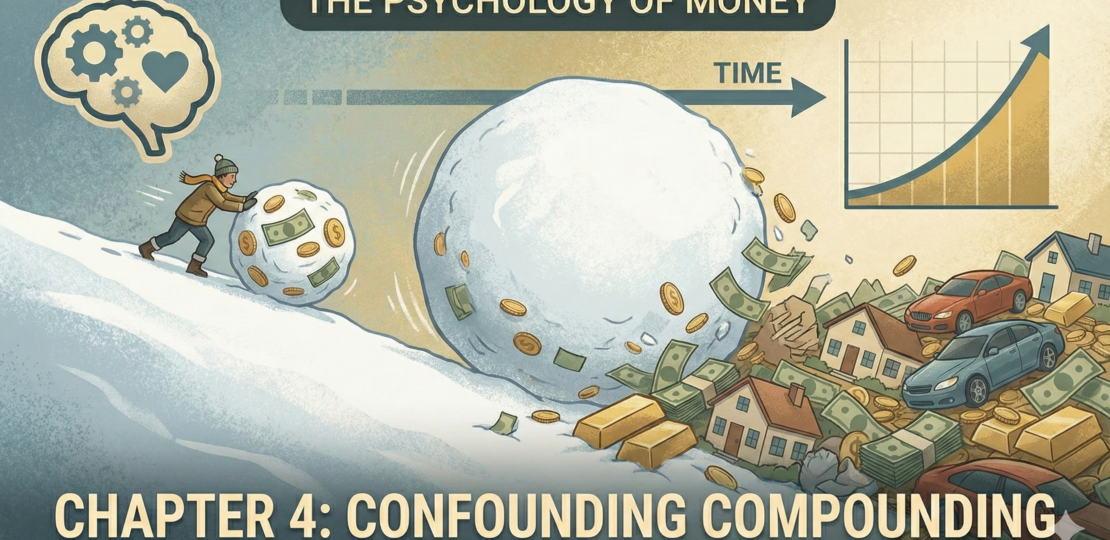

The most striking thing about compounding is not how powerful it is, but how poorly our minds grasp it. Outcomes that unfold slowly for decades and then explode late in the process feel unnatural to us. The fact that the overwhelming majority of Warren Buffett’s wealth arrived after his mid-sixties sounds absurd, yet it is mathematically ordinary. Small, sustained advantages, given enough time, produce results that feel disproportionate only because we underestimate duration.

The contrast between Buffett and Jim Simons sharpens this point. Simons achieved returns that dwarf Buffett’s on an annual basis (66% vs 22%), yet ends up far behind in absolute wealth (21 billion vs 84.5 billion). Skill matters, but time compounds skill into something visible. Without time, even extraordinary brilliance struggles to leave a mark. This is why obsessing over peak performance misses the deeper lesson: endurance is often more valuable than intensity.

Compounding also explains why tiny, almost boring inputs can shape enormous outcomes. Just as subtle shifts in Earth’s orbit can trigger or end ice ages, small changes repeated consistently accumulate into irreversible trajectories. This principle extends well beyond finance. Habits, learning, and careers follow the same quiet math. One percent improvements look laughable in isolation, but transformative when allowed to stack uninterrupted.

The real danger is not ignorance, but impatience. We chase high returns and quick results because waiting feels like inaction. In reality, the ability to wait is an advantage most people never cultivate. Investing, at its core, is not about constantly doing something smarter. It’s about resisting the urge to interfere while time does the work.

RELATED POSTS

View all