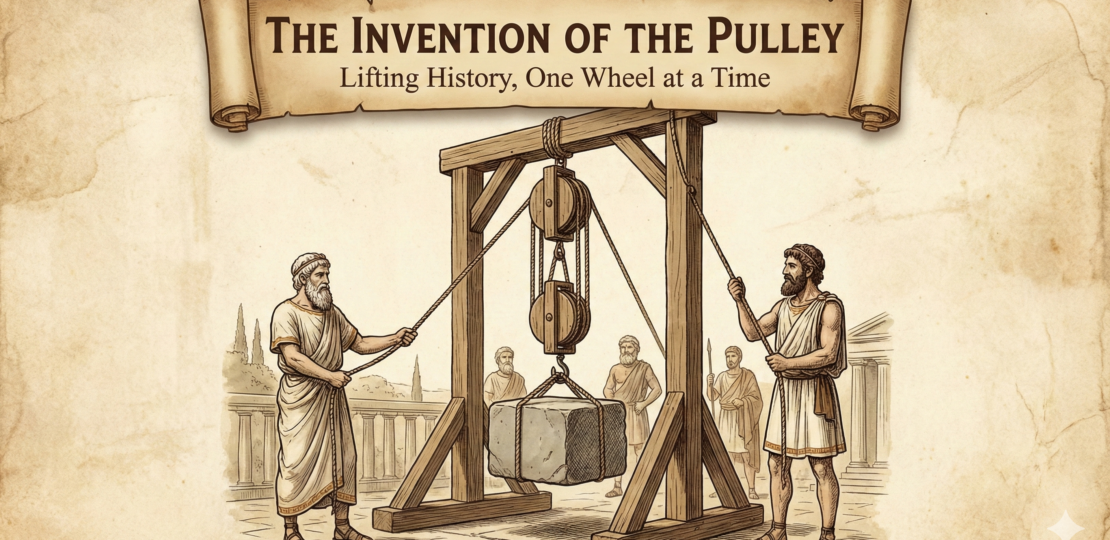

A pulley is a wheel with a groove and a rope. That description feels almost insulting to how useful it is. With that tiny addition—a rotating guide for a rope—humans learned how to lift stones, raise sails, and build upward instead of outward. The pulley didn’t make us stronger. It made us smarter about effort.

The core trick is simple. By redirecting force, a pulley lets you pull down to lift up, aligning work with gravity instead of fighting it. Add more pulleys, and the load gets shared. Each extra wheel trades force for distance, turning brute strength into endurance. The math behind it is clean, but the intuition came first: pull longer, lift easier.

Engineering refined the pulley by worrying about things that don’t show up in drawings. Friction steals effort. Rope stretches. Wheels wear. In real systems, efficiency matters as much as theory. That’s why cranes, elevators, and even gym machines obsess over bearings, materials, and alignment. The pulley looks innocent, but it punishes sloppy design.

The pulley also changed how engineers think about direction. Work doesn’t care which way force is applied; only energy balance matters. This idea echoes through modern engineering, from power transmission to signal routing. You don’t need to attack a problem head-on. You can come at it sideways and still win.

Simple machines like the pulley survive because they encode deep truths in humble forms. They remind us that intelligence often lies not in adding complexity, but in arranging what already exists so effort finally makes sense.

RELATED POSTS

View all