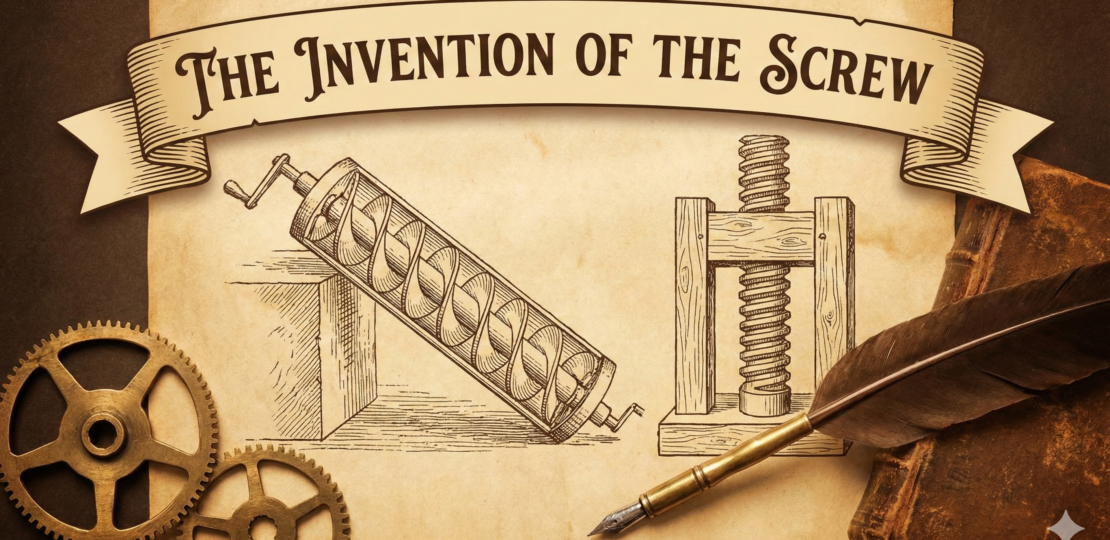

The screw is almost offensively simple. A spiral wrapped around a cylinder. That’s it. No electronics, no moving parts once it’s in place, no need for explanation beyond a sketch in the sand. And yet, nearly every engineered object you’ve ever touched—from a phone to a bridge—depends on this humble idea staying exactly where it’s put.

What the screw really does is translate rotation into linear force. By stretching a long ramp around a small circle, it lets weak hands generate enormous holding power. One turn at a time, force accumulates. This is mechanical advantage in its purest form: patience amplified by geometry. Ancient civilizations understood this intuitively long before formal physics gave it equations.

Engineering matured the screw by caring about details that look trivial until they aren’t. Thread pitch determines speed versus strength. Material choice decides whether it bites, deforms, or snaps. Even the angle of the thread balances friction against efficiency. None of this is flashy, but all of it matters. Failure often isn’t dramatic—it’s a slow loosening, a vibration, a forgotten washer.

The screw also shaped how engineers think about assembly and repair. Unlike glue or welding, it allows reversibility. Things can be taken apart, examined, improved, and rebuilt. That idea—designing for disassembly—quietly underpins maintenance, sustainability, and learning itself. You can’t study what you can’t open.

Invention doesn’t always mean complexity. Sometimes it means discovering a shape that cooperates perfectly with human hands and physical law. The screw endures not because it is clever once, but because it remains useful forever—proof that the simplest ideas, properly aligned, can carry astonishing weight.

RELATED POSTS

View all